The Logic of Egyptian Terms: Part I

I explore what it means to truly decolonize an astrological method by restoring cosmological significance to the Egyptian Terms that Ptolemy dismissed outright as irrational due to their lack of symmetry. However, when viewed through the lens of Egyptian cosmology, it becomes clear that the asymmetrical division of Terms reflected the cosmic order, known as Ma'at. Rather than being mathematically coded, the Egyptian Terms were encoded with ritual meaning and divine resonance, which provides a richness to astrological interpretation that Ptolemy disregarded out of his distaste for asymmetrical division.

Zora Lysara

6/6/202515 min read

The Logic of Egyptian Terms: Part I

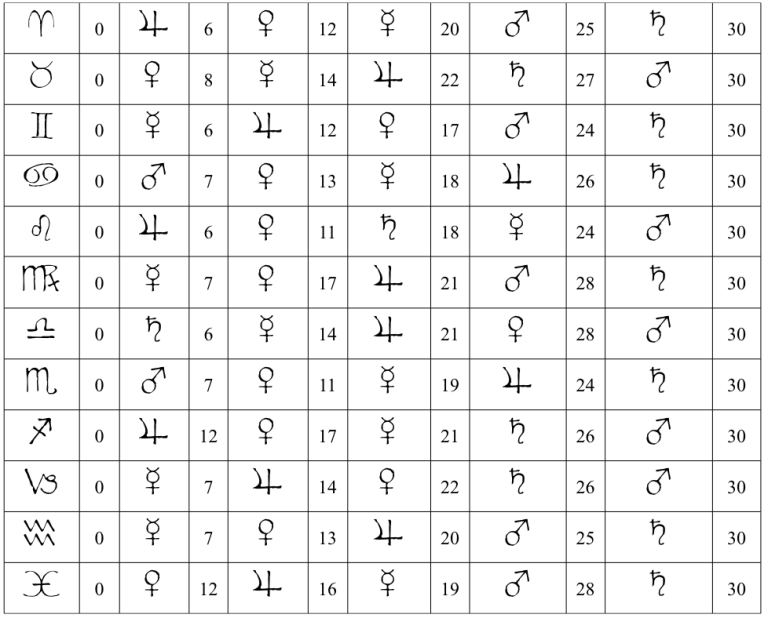

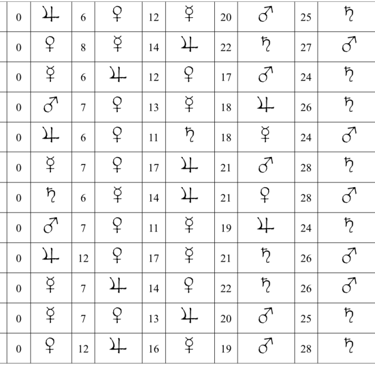

Before I can discuss Egyptian Terms, I need to first discuss what Terms themselves even are. Within Western astrology (tropical), a planet may be dignified by Term, and Terms are fivefold divisions of each of the 12 zodiac signs into bounds ruled by specific planetary Term Lords: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter. When a planet is in its own Term, it is said to hold minor dignity, which can ofset a difficult placement (like Saturn in fall in Aries) by providing the planet a way to express at least some of its energies in beneficial ways.

That is usually where astrologers stop with Term Lords, which is what makes what I do with Fusion Astrology so unique. I trace the Term Lords across the chart to understand how those energies are best expressed in someone’s chart. For example, if Saturn is in Aries in Mars’s Term in the 8th house, then I locate Mars in someone’s chart to determine how Mars’s energy impacts Saturn in Aries in that house.

To further this example, let’s say that Mars is in Scorpio in Mars’s Term in the 3rd house. By being in rulership (Mars is the traditional ruler of Scorpio) and in its own Term, Mars directs Saturn’s energies in the 8th house (where it is in Mars’s Term) by refining the way that the person communicates with others. Mars placed here, directing the energies of Saturn, suggests that the person struggles to avoid aggressive and violent communication with other people, especially concerning the resources of others, and needs to learn to channel their intensity into healthier dynamics by mastering communication skills.

Essentially, the way I read planets in Terms paints a picture of the different types of lessons a person is here to learn during their lifetime. While Chiron is the core wound, I have found that the Terms demonstrate the smaller wounds that need to be healed before the core wound can really start to close.

So, in this example, the person would need to learn to communicate in healthy ways about the resources that others have in order to heal a smaller wound in themselves concerning their tendency to view others with jealousy. Saturn in Aries in Mars’s Term in the 8th house suggests that they need to master their impulses and tendency to accuse others of hoarding resources due to Mars’s placement in its own Term in Scorpio in the 3rd house.

This lends a specificity to my interpretations that I have found, through countless trial and error reading hundreds of charts, always resonates with my clients. The greatest benefit, to me, of using Terms this way, really allows the specificity of astrology to shine in a way that negates the claims that naysayers of the discipline often make about how “vague” it is and how there is something in all interpretations that applies equally to everyone.

But the way I interpret via Terms isn’t the main point of my article today. Instead, I want to discuss what the Egyptian Terms actually are, and what the logic is that underlies them – something that no astrologer has really attempted to do since Ptolemy declared the Egyptian Terms “irrational” and essentially threw them out without a second thought.

For those unfamiliar with this part of astrology, there are three sets of Terms that an astrologer can choose to use: Chaldean, Ptolemaic, and Egyptian Terms.

The Chaldean Terms are technically the easiest set to understand, as they are based on the Chaldean planetary speed and order of distance from Earth (Saturn – Jupiter – Mars – Venus – Mercury).

The Ptolemaic Terms were developed by Ptolemy, who found both the Chaldean and Egyptian Terms to be “irrational” due to the uneven distribution of the terms around the zodiac wheel. So, he redistributed the terms so that each of the five term lords – Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury – had a bound of 5-7 degrees in each of the 12 signs.

The Egyptian Terms, in contrast to the Chaldean Terms, were not based on any discernible mathematical principle. Because of that, few astrologers have ever really tried to do much with them.

However, because I am a pagan polytheist and work with Egyptian gods (among other pantheons) in my spiritual practice, I started wondering if maybe the reason that no one has decoded the meaning of the Egyptian Terms is because people keep trying to find mathematical patterns that simply do not exist within the terms as the Egyptians understood them.

Since I specifically honor the Memphis Triad (Ptah - Sekhmet - Nefertem), I will be referencing these three deities alongside a couple other Netjeru of the Memphis (aka Memphite) tradition to explain the way that the Egyptians most likely divided the Terms as they understood them.

Before I do that, however, it is important to understand something very specific about Egyptian cosmology. The way that the ancient Egyptians understood the universe was through a ritual process of keeping the Sun itself in the sky. Their day began with rituals that honored the rising of the Sun, there were noon rituals that honored the height of its path, and there were sunset rituals that staved off the threat of non-existence itself (it has a name, but it isn’t proper to say or write it when you honor these gods, as it is a threat to existence itself).

Every single day, for the ancient Egyptians, was a ritual procession. Every rite they performed was for the sole purpose of keeping the Sun rising every day. Within the Memphis tradition, Ptah is the cosmic intellect, the primordial divine order, the creator god in which all other gods existed, the origin of light, the divine mind through which the Sun itself (Ra) is conceived.

Because Western astrology is typically done through a Hellenistic lens, some comparative mythology is required to fully explore what this means. For the Egyptians, Ptah would have roughly equated to Jupiter, which means that every Term that falls within Jupiter’s domain would have been understood, by astrologers of the Memphis tradition, as being under the reign of Ptah.

Ptah’s counterpart, the gatekeeper of the underworld and the finality of limitations, is Sokar. He is heavily associated with tomb entrances and resurrection, and he is heavily associated with digging ditches and canals alongside punishing the souls of evildoers. As such, Sokar would have been understood, through the lens of comparative mythology, as a deity very similar to Saturn.

What gets really interesting here is that Mars and Venus take on different gender polarities within the Egyptian cosmos in the Memphite tradition, as Sekhmet (Ptah’s wife) most aptly captures the warrior energy of Mars and Nefertem (their son) best captures the aesthetic sensibility of Venus.

Sekhmet is one of the Eyes of Ra, and she is the personification of divine rage. One of the most well-known myths of her rage concerns Ra, who is angry because humans have rebelled against his authority. In his anger, he sends Sekhmet to slaughter the humans that have defied him. However, her rage is so complete that she begins slaying men indiscriminately. At this point, Ra grows concerned because even he cannot quench her rage. So, instead, he has red beer poured across the land (because it resembles blood), and Sekhmet drinks it, thinking that it actually is blood. She drinks so much that she becomes intoxicated, and it is only when she is completely drunk that her bloodlust subsides and reason returns. Of all the Egyptian gods, Sekhmet’s fury is the one that comes closest to matching the ferocity of Mars.

Nefertem, on the other hand, is the embodiment of the lotus petal, the flower that is born pure in the middle of filth. The lotus itself is a global symbol of beauty and purity, and Nefertem is the Egyptian god of perfume. He is a lesser known god because, even today, few pagans honor the Memphis triad rather than one of the other two triads (Abydos/Philae tradition, which honors Osiris-Isis-Horus or Thebes tradition, which honors Amun-Mut-Khonsu). Nefertem is known as “the lotus-bloom who rises from Ptah,” making him a very physical deity and, thus, the closest Egyptian equivalent to Venus.

The closest Egyptian equivalent to Mercury, of course, is Thoth – more accurately called Tehuti – who is a lunar god who most people who have any understanding of Egyptian cosmology at all view as the god of knowledge. He is the scribe of the gods who keeps the records of fate within his divine library (it is my belief that the concept of the akashic records may have originated with someone aware of Tehuti’s role as the scribe of the gods).

So, to recap, the closest equivalents to the Greek Term Lords, via the Egyptian gods of the Memphis tradition, are Ptah (Jupiter), Sokar (Saturn), Sekhmet (Mars), Nefertem (Venus), and Tehuti (Mercury).

That’s the first critical component of understanding the Egyptian Terms, which are cosmologically derived rather than mathematically precise. Within Egyptian cosmology, everything is ordered according to Ma’at (both the principle of order and a goddess herself) and existence itself unfolds through the magic of the spoken word, known as heka. Words have a great deal of power and meaning; heka is the backbone of Egyptian cosmology alongside the principles of Ma’at and its obverse.

As such, the Egyptian astrologers would have split the Term Lords into an understanding that reflected their daily ritual cosmological procession that was required to keep the Sun in the sky. There is no mathematical precision to the Egyptian Terms because the Egyptians were less concerned about math and more concerned with ensuring the continuation of the divine order.

Once you understand that, you can start to see the numerological logic behind the division of the Terms in each of the 12 signs. Each sign was split unevenly because, for the Egyptians, a lack of symmetry was actually proof of Ma’at. Uneven numbers were sacred because they reflected a cosmic order that was capable of renewing itself because it was unbalanced. A lack of balance provided the necessary tension for dynamic movement, which is clearly seen through Egyptian cosmological principles.

In all three traditions, the world begins with one creator – Ptah in the Memphis tradition – who divides himself to create a total of three beings; a division doesn’t produce Ptah and one other being but Ptah and two other gods. By dividing himself, Ptah participates in a threefold division that allows for the manifestation of physical reality itself. The reason such a threefold division occurred, according to Egyptian cosmological principles, is that when odd numbers are divided, a residual trace is left behind, what is referred to as the ka.

To make this clearer, we often divide our understanding of a person into three pieces: body, mind, spirit; id, ego, superego; mind, heart, soul. Threefold division is a constant found globally, so it is not surprising that the Egyptians understood that Ptah divided a single being into three separate forms. The Egyptian threefold division of Ptah can be loosely understood as a division into soul, spirit, and substance.

Odd numbers were, as a result, all considered extensions of Ma’at and extremely significant in ritual use. Even numbers also had their importance, but they were seen as potentially stagnant and destabilizing points. Since none of the Egyptian Terms have less than a 2° range, we’ll focus on what the cosmological significance of each of the numbers of those ranges are.

Two

Two is a number that is inherently unstable, even if it represents an origin point, because it represents the presence of two forces that are locked in stasis. Stasis was not ideal, as the Egyptians prioritized rituals that ensured the Sun rose and set every day. Stasis would prevent that, and two was most likely viewed as a preferred number for the antithesis of Ma’at (isfet, or disorder).

Three

Three is a holy number that represents the unfolding of the cosmic itself. It is the origin point of cosmic creation, manifestation with dynamic and polarizing movement that ensures its continuation through the presence of tension.

Four

Four holds sacred resonance through its ability to limit and contain. Four maps the contours, or the boundaries, of ritual spaces. It is a number of containment; it holds forms and shapes limits. The four cardinal directions are the limits of the physical world, temples were typically built with four pillars to provide a contained structure for ritual work, and it was used for agricultural timekeeping. Four is a crucial number that defines both physical and spiritual boundaries.

Five

Five is the number, in Egyptian cosmology, that represents the five epagomenal days associated with the birth of the gods. In practical terms, these five days were added to the end of the year to ensure the Egyptian calendar stayed in alignment with the solar cycle. These five days took on religious significance, and, if you consider that five can either be a combination of one and four or two and three, there is an added resonance to the number five that suggests both the birth of the gods (one unfolding into three) and the anchoring of the physical world with limitations and boundaries (two multiplying into four). As such, five may be the number that best corresponds with the Hermetic principle of “as above, so below” because the five epagomenal days seem to represent not only the birth of the gods but also the birth of the universe itself.

Six

Six is a number suggestive of harmony that is only temporary, an echo of creation that lacked substance. While six is a doubling of three, the fact that six is an even number would have been looked at by the Egyptians as a disruption of Ma’at because there was no generative power in even numbers. Six represents closure without creation, containment without blessing. As a combination of two and four, six holds the instability of isfet against the structural soundness of four, a paradoxical number of harmony without balance. As a combination of one and five, six holds origin but lacks continuation, as one is the number associated with the beginning of existence itself while five is associated with the birth of the gods. Six holds the essence of those beginnings but is stuck at the origin, unable to flow dynamically into physical manifestation.

Seven

Seven is a vital number within Egyptian cosmology, best represented by a myth that comes from the Late Period concerning Isis and Horus. After Set killed Osiris, Isis went into hiding with her son, Horus, accompanied by seven divine scorpions. These scorpions were spiritual entities imbued with heka that carried divine venom within them, and they acted as bodyguards for Isis and Horus, who went into hiding to avoid Set’s murderous rage. When they entered the town Per-Sui, Isis knocked on the door of a wealthy woman seeking shelter. Unable to recognize Isis in the form she had assumed, the woman slammed the door in Isis’s face, which greatly enrages the seven scorpions. The seven scorpions decided to take vengeance for Isis by gathering all of their venom together into a single, lethal dose of poison that one scorpion used to sting the woman’s young son. This caused the boy to become gravely ill, as he was essentially stung by the venom of all seven scorpions at one time. When Isis learned of this, she decided to take pity on the woman and revealed her divine identity before reciting a healing incantation (a form of heka) where she called back the venom of all seven scorpions and restored the boy to full health.

This particular story is loaded with the cosmological significance of the number seven, shown first, of course, by the scorpions themselves. Seven is also the threshold between life and death, illustrated by the scorpions’ willingness to kill to protect Isis and Isis’s decision to restore the boy to full health despite the offense committed against her. The concepts of both justice and mercy are illustrated by the myth, giving that same resonance to the number seven.

As such, seven is a number that represents true harmony, as it holds the threshold but continues past it. That can be seen in the numbers that combine to form it, as one and six combine creation and its echo, two and five combine the birth of isfet with the birth of the gods (and thus the birth of Ma’at), and three and four combine the origin of the universe with the physical limitations that constrain it. Seven is, in essence, a number that brings life and death into balance, puts Ma’at and isfet on either side of the scales, and represents the liminal threshold between existence and its antithesis.

Eight

Eight is an intriguing number because, even though it is a pure doubling of the number four, it represents entities that existed before creation. Within Hermopolis, also known as Khemenu, the worship of eight primordial deities known as the Ogdoad was practiced. The Ogdoad is composed of four male-female divine pairs: Nun and Naunet, Heh and Hauhet, Kek and Kauket, and Amun and Amaunet. Each of these pairs represent a specific primordial force: Nun and Naunet were the primordial waters, Heh and Hauhet the infinity of space or eternity itself, Kek and Kauket darkness and obscurity, and Amun and Amaunet the hidden, unseen force. As a group, the Ogdoad are the entities that existed prior to creation, prior to Ra, prior to Ma’at itself. They are, in essence, the precursors of existence, the force of primordial chaos that exists before all things yet holds within it the potential for the infinite expansion of existence itself.

In a way, then, eight can be viewed as a number that, as a doubling of four, represents the limitations of primordial chaos. It is, like all even numbers within Egyptian cosmology, a paradox that sustains itself through its inability to generate. What is intriguing about eight are the other combinations that comprise it: one and seven, two and six, three and five. One and seven show eight as a combination of origin and threshold, two and six as the latent potential before physical manifestation and true harmony, and three and five as the combination of physical manifestation and the birth of the gods. In essence, eight holds the liminal threshold between macrocosm and microcosm, chaos before emergence.

Nine

For the cosmological significance of the number nine, we have to look to Heliopolitan theology (rather than the Memphis tradition), as it was within Heliopolis that the Ennead, or the divine nine, was worshipped. The Ennead of Heliopolis consisted of Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys, and represented a cosmic cycle of divinity dividing itself until physical incarnation became feasible. It was through this structure that divine kingship was devised, the belief that the pharaohs were themselves a physical embodiment of the divine. As such, nine is the bridge between the macrocosm and the microcosm, the liminal corridor between pre-existence and physical incarnation.

This can be seen in the numbers that can be combined to form nine: one and eight, two and seven, three and six, four and five. One and eight allows the latent potential of primordial chaos (the Ogdoad) to become actualized. Two and seven combine polarity with harmony, suggestive of the Hermetic principle that paradoxes are illusions that resolve themselves (the principle of polarity). Three and six combine the physical manifestation of the universe itself with its echo, and four and five combine the structural limitations of physical existence with the birth of the gods. The combination of four and five are especially suggestive of the restrictions that the gods were subjected to when they took physical form; in other words, a god that stepped into the physical world to take up the mantle of divine kingship (as pharaoh) was forced to exist within the constraints placed on physical existence.

Ten

Ten was considered a doubling of five, a number of completion. That is clear in the numbers that can be combined to form it: one and nine, two and eight, three and seven, four and six, five and five. As one and nine, ten combines the spark of origin with the full manifestation of the gods in the physical world – in other words, a complete cycle. With two and eight, ten is both the instability of isfet’s origin and the stable, if inert, potentiality for existence. As a combination of three and seven, ten is both the origin of physical existence and the potential for its ending, the entrance to both life and death. As four and six, ten structures physical existence through the limitations of four and the stable echo of creation in a harmony that never fully resolves. As a doubling of five, the number representing the birth of the gods themselves, ten is a number of completion, evidence that the birth of the gods is itself a stable occurrence.

The Unusual Odds: Eleven and Thirteen

Eleven and thirteen were unusual odd numbers in Egyptian cosmology, as they are both numbers that go beyond the completion of the cycle represented by the number ten. Eleven, specifically, is a number of excess, a surplus that disrupts harmony instead of preserving it. In the Books of the Dead, where the underworld is divided into twelve hours, the eleventh hour is portrayed as the hour where judgment is almost complete but danger is still active. This phrase has echoed into our own world, where we use the phrase “the eleventh hour” with almost the exact same resonance, the exact same meaning to almost achieve something but with the understanding that doing so is fraught with difficulty and may prove impossible.

Like eleven, thirteen also disrupts sacred harmony. For Egyptians, twelve was a number much like ten, a number that represented cyclical completion. That can be seen in how the Egyptians divided days and nights into twelve hours, the judging of the soul itself into twelve hours, and the fact that there were twelve deities of the Duat (or underworld). Thirteen breaks this cycle, and, as a number that breaks a cycle, was considered antithetical to Ma’at. In addition to that, one of the myths concerning Osiris is his dismemberment by Set, who is said to have cut Osiris into fourteen pieces but only thirteen were ever recovered. In this way, thirteen is a number that not only breaks a cycle but prevents the completion of another. Thirteen is a number of transgression, of forbidden knowledge, and of creation through pain as Set dismembered Osiris to establish himself as the foremost authority of the divine. In this way, thirteen is the presence of too much divinity, too much spiritual pressure exerted in the physical realm.

End of Part I.

In Part II, I’ll turn to a discussion of how this cosmological numerology is reflected in how the Egyptians divided the Terms across the signs of the zodiac, and how that cosmological application demonstrates the ritual significance of each division. While Ptolemy found the Egyptian Terms nonsensical, the Egyptians themselves clearly made very intentional divisions that reflected their own cosmological understanding of the world. By applying the theology that the Egyptians themselves used to the way that their astrologers divided the Terms, I am doing decolonial work that restores dignity to a system, a dignity that Ptolemy refused to honor.

©The Knotty Occultist 2020-2025