Precision Before Ptolemy: Manilius's Poetic Geometry

Manilius, an astrologer writing in 1st century CE Rome, is often dismissed as an oddity. His "Astronomica," a five-book astrological treatise written in verse, has long been treated as a curiosity rather than a serious source. But as a historian trained in "reading against the archive," I take poetic sources seriously. Applying historical method to Manilius reveals an intricate system of astrology rooted in geometric precision, one that not only predates but often surpasses Ptolemy. His work challenges the modern assumption that only five aspects were known in antiquity and shows that the debate over orbs in trines and squares is, in fact, an ancient argument among astrologers.

Zora Lysara

6/18/202516 min read

Precision Before Ptolemy: Manilius's Poetic Geometry

All excerpts come from the 1697 English Text The Five Books of Manilius which is freely accessible via the Internet Archive. The English text is a translation of Manilius’s Astronomica, which was written sometime in the 1st century CE, predating Ptolemy by 100 years or more.

Reading Manilius: The History of Astrology Hidden in Verse

Reading through Manilius is a difficult task, as he wrote his astrological treatise as a series of poems composed originally in Latin hexameter. Most astrologers, if they contend with Manilius at all, tend to view his poems as an oddity and do not really take him seriously as an astrologer. However, one of my specialties as a historian is untangling sources, reading between the lines to see what’s being said. It is sometimes called reading against the archives, as it is primarily used to discern how oppressed people actually interacted with their oppressors when the only historical sources we have are written by their oppressors. It is a method used to make the silences of the past speak, a method informed by Michel Trouillot’s 1995 book, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History.

Sometimes, what reading against the archives actually looks like is paying attention to the sources that other people largely write off as irrelevant, unusual, or uncredible. In my own historical research, which largely concerns Espiritiismo during the Cuban 1868-1878 Ten Years’ War, this means paying attention to periodicals where mediums claimed to have messages from the spirits of certain politicians that had communicated their desire for freedom. Whether these mediums were actually legitimate or not is actually historically irrelevant, because what matters is that the people who read these messages believed that they were and thus acted as if they were. Whether spirit communication is possible isn’t historically relevant; what matters is that belief shaped action, and those actions rippled across time.

In the case of Manilius, he wrote five books on astrology, and he wrote them using poetry on purpose. He was intentionally encoding knowledge so that only those who paid close attention to his words would understand him. He says this himself, explicitly, in Book II:

Whilst on these Themes my Songs sublimely soar,

And take their Flight, where Wing ne’re beat before;

Where none will meet, none guide my first Essay,

Partake my Labors, or direct my way,

I rise above the Crowd, I leave the Rude,

Nor are my Poems for the Multitude.

Heaven shall rejoyce, nor shall my Praise refuse,

But see the Subject equall'd by the Muse;

At least those favour’d few, whose Minds it shows,

The Sacred Maze, but ah! How few are Those!

Gold, Power, soft Luxury, vain Sports and Ease

Possess the World, and have the luck to please:

Few study Heaven, unmindful of their state,

Vain stupid Man! But this it self is Fate.

Many have interpreted this as vanity on Manilius’s part, and it is easy to see why. Manilius often refutes the theories of others. But he was also intentionally writing for people who would think through astrology in a different way – why else would he write a technical treatise in poetic verse? He had to have known that it would have been seen more as a curiosity than taken seriously, and he probably counted on that.

It is a delicious irony: Manilius is both conceited and humble. Conceited, because he definitely considered his method of astrology superior to the methods practiced around him. Humble, because he knew that his work wouldn’t be treated seriously. He wasn’t a stupid man. If he had wanted fame, then he would have written in prose. But he wasn’t seeking fame.

He tells us plainly: this is a method preserved for those who care to read closely. And when you do read closely, what emerges is a careful, geometrically rigorous astrological system—one more precise than Ptolemy’s.

Aspects

Most traditional astrologers today accept only the five aspects Ptolemy outlined in his Tetrabiblos: conjunction, sextile, square, trine, and opposition. But if you read Manilius closely, you’ll see that he describes two additional aspects that modern astrologers now call the inconjunct (or quincunx) and the semi-sextile—both more than 100 years before Ptolemy ever wrote his system down.

Manilius referred to what we now call quincunxes as “6ths” and described semi-sextiles as “contiguous signs.” Crucially, he didn’t view these as harmonious the way modern astrologers sometimes do. Quite the opposite: he described them as dissonant, uninterested in contact or affinity. In other words, if astrologers today actually took Manilius seriously, they’d realize he was working with at least seven aspects, not just the five that tradition attributes to antiquity. In Book II of Astronomica, he writes:

From Signs unequal any way remove

All Thoughts of Union, they’re averse to Love:

Thus never think between the Sixths to find

An Intercourse, nor hope to see them kind;

Because the Lines, by which we mark their place,

In length unlike stretch thro’ unequal space.

For take the Zodiack, from the Ram begin,

And thence on either side extend the Line

To meet the Sixth from Aries, then dispose

A Third, and let the Three in Angles close;

Between the Two first lines Four signs are found;

The Third includes but One, for that fills up the Round.

This passage is often misread as describing oppositions, but opposing signs form a clean 180° line with six signs between them, divided equally. Manilius specifically emphasizes the unequal nature of the space he’s describing. What he outlines is a triangular configuration formed by Aries, Virgo, and Scorpio: From Aries to Virgo: four signs (Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo). From Aries to Scorpio: four signs (Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn, Sagittarius). From Virgo to Scorpio: one sign (Libra).

That’s a 4–4–1 structure, not a 6–6 opposition. He calls this an “unequal” relationship; we’d call it a quincunx today. And the fact that he follows this description with a separate treatment of oppositions shows that he understood these as distinct concepts. Manilius also referred to contiguous signs–those that follow one another in zodiacal order–as dissonant. Since each sign spans exactly 30°, these signs are 30° apart, corresponding to what modern astrologers call the semi-sextile. In Book II, he writes:

In Concord no Contiguous Signs agree,

For what can love when ‘tis deny’d to see?

They to themselves, which they behold alone,

Their Passion bend, and all their Love’s their own.

Alternately or different Kinds they lie,

One Male one Female fill the Round of Sky.

It’s clear from this passage that Manilius viewed contiguous signs as unable to see each other, too close to connect. What’s fascinating is how this directly contradicts the modern tendency to treat semi-sextiles as subtly harmonious. The term itself borrows legitimacy from sextiles (60°), which are considered positive. For Manilius, however, the semi-sextile was not a weakened harmony but a failed connection.

Manilius was clearly working with more than five aspects. He described both the inconjunct/quincunx and the semi-sextile over a century before Ptolemy wrote his Tetrabiblos, though he used different names. Manilius referred to at least seven distinct aspect types in Astronomica: conjunction, sextile, square, trine, opposition, unequal signs (inconjunct/quincunx), and contiguous signs (semi-sextile).

We’ll return to aspects later, but first, we’ll turn to what may be the most geometrically precise part of Manilius’s entire treatise: the dodecatemorion.

Dodecatemorion

He introduces the Dodecatemorion – or the signs each split into 12 equal parts – in Book II:

Now with expanded Thought go on to know

A Secret great in life, tho’ small in show;

For which our scanty Language, poor in words,

No single fit expressive Term affords,

But Greek supplies, a Language born to frame

Fit Words, and show their Reason in their Name.

...

‘Tis Dodecatemorion thus describ’d

Thrice ten Degrees with every Sign contains

Let Twelve exhaust, that not one part remains;

It follows straight that every Twelfth confines

Two whole, and one half Portion of the Signs:

These Twelfths in Number, as the Signs, are Twelve,

And these the wise contriver of the Frame

Plac’t in each Sign, that all may be the same.

The World may be alike, each Star may guide

And every Sign in every Sign preside;

That all may govern by agreeing Laws,

And friendly Aids be mutual as their Cause.

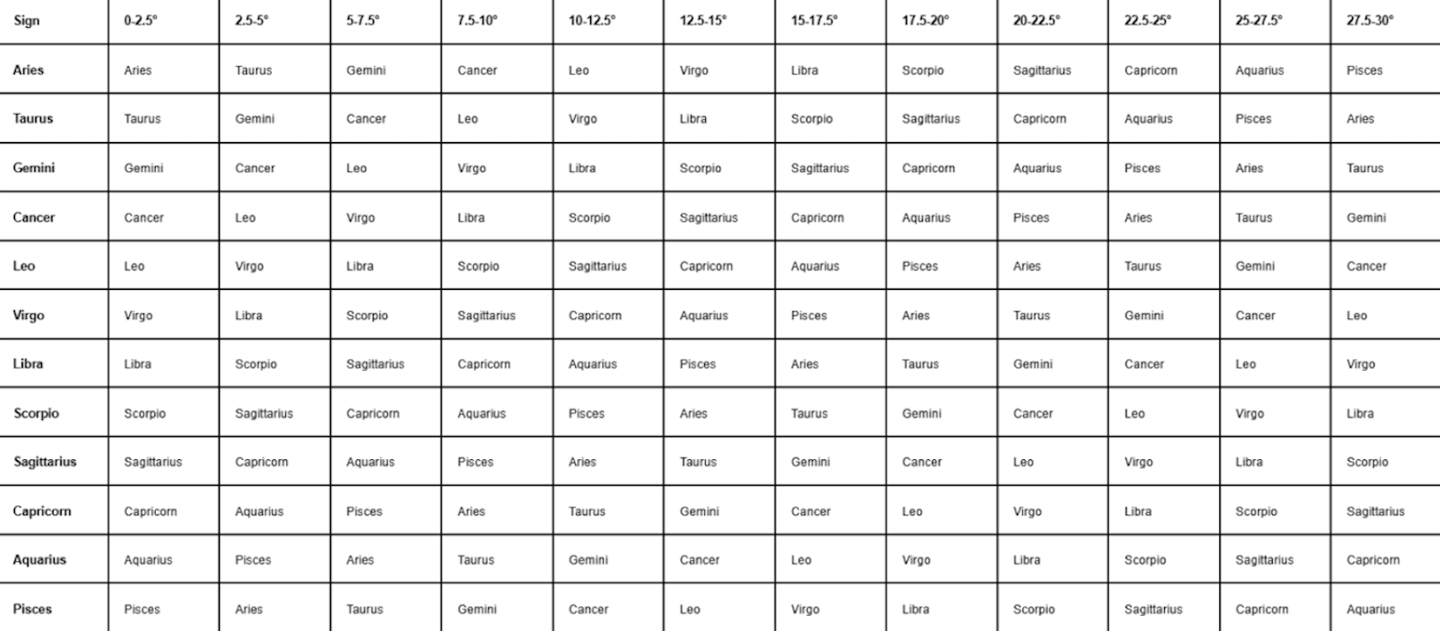

In short: every sign contains twelve subdivisions, each 2.5° in length. The first dodecatemorion (or “twelfth-part”) belongs to the sign itself, and the remaining eleven proceed through the zodiac in natural order. For example, Aries contains a portion of every other sign, but the first 12th of Aries belongs to Aries, the first 12th of Taurus belongs to Taurus, the first 12th of Gemini belongs to Gemini, and this repeats for all 12 signs.

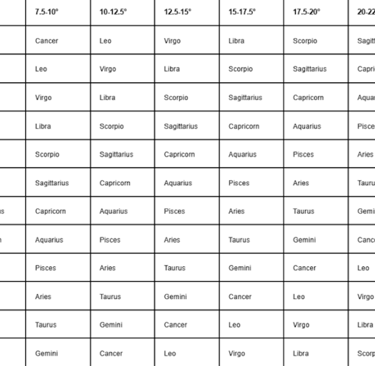

The Dodecatemorion of All 12 Signs: A Reference Chart

The table below pictures the Dodecatemorion as outlined by Manilius: each sign of the zodiac is divided into twelve equal parts (2.5° each), starting with itself and proceeding through the signs in order. This framework predates Ptolemy and reveals a micro-zodiac embedded within every sign.

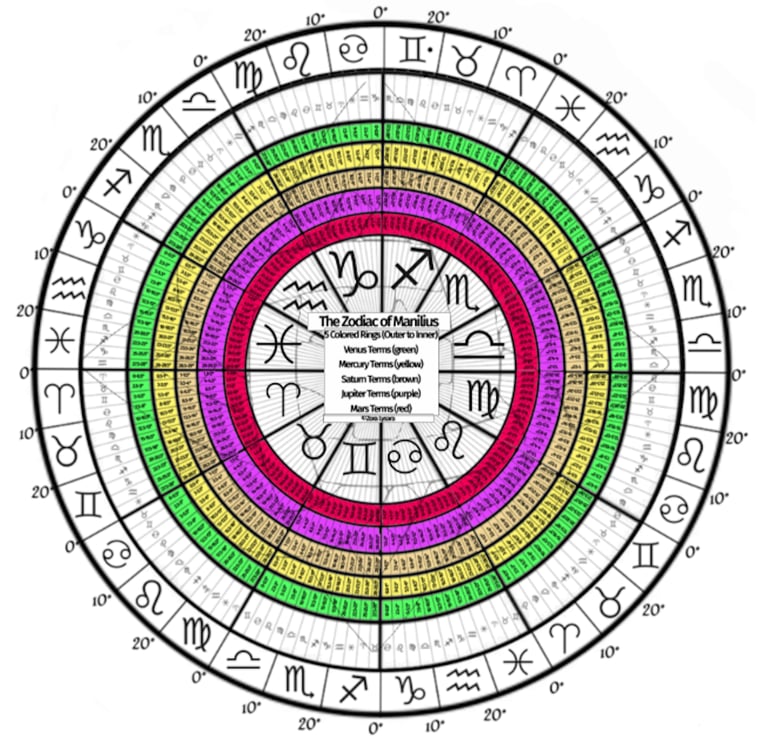

Stadia

Manilius further subdivides the Dodecatemorion by assigning each half degree (a total of 720) to 1/5th of every 12th to the planets “in their proper course” which he reveals in Book I as Venus - Mercury - Saturn - Jupiter - Mars. In Book II:

In every Twelfth a Twelfth the Planets claim,

The Thing is different though we use the Name;

‘Tis thus describ’d. Five half degrees do lie

In every Twelfth, Five Planets grace the Sky,

And every Planet in its proper Course

One half Degree possessing there exerts its Force.

Manilius clarifies this ultra-fine subdivision in Book III of Astronomica:

Seven Hundred Twenty Stadia fill the Round,

No more in Day, no more in Night are found.

This confirms that Manilius divided the zodiac into 720 parts, each half a degree wide. These “stadia” are micro-terms of astrological influence, a system so precise it rivals modern methods. While he introduces the dodecatemorion and stadia in Book II, he reserves his full explanation of decans for Book III.

Decans

It is in Book III of Astronomica that he specifies the decans themselves and how they are divided, making it very clear that the decans, dodecatemorion, and stadia are separate from each other. In Book III:

Thus Rule the Twelve, these Powers they singly own,

And these would give if they could work alone.

But none rules All its own degrees, they joyn

Their friendly forces with some other Sign,

As ‘twere compound, and equal parts receive,

From Other Signs, as they to Others give:

Thus each hath Thirty parts, and each resigns

Two Thirds of those degrees to other Signs:

We call these portions (Art new words will frame,)

The Tenths, the Number doth impose the Name.

Here, it is clear that Manilius is discussing the Decans, as he calls them the Tenths. It is important to clarify, however, that he misidentifies the number of total Decans in the zodiac as 30 – there are actually 36 (3 decans per sign). From this point, he starts to identify which Decans belong to which sign:

Aries’s Decans: Aries, Taurus, Gemini

For instance, Aries shakes his shining Fleece,

And governs the First Ten of his Degrees:

But next the Bull, and next the Twins do claim

The second, and third Portions of the Ram:

Thus three times Ten Degrees the Ram divide,

And He, as many others as preside

In his Degrees, so many Fate affords

His proper Powers being temper’d by his Lords.

Taurus’s Decans: Cancer, Leo, Virgo

Thus lies the Ram, next view the threatening of Taurus Bull,

His case is different, he hath none to Rule:

For in his First Ten Parts the Crab’s obey’d,

i’th Second Leo, and i’th Third the Maid.

Yet he seems stubborn, and maintains his Throne,

And all Their Powers he mixeth with his Own.

Gemini’s Decans: Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius

The feeble Twins just Libra’s Scales possess,

Then Scorpio, and the rest of their Degress

Bold Sagittarius subjects to his flame,

With Bow full drawn, as to defend his claim.

Cancer’s Decans: Capricorn, Scorpio, Sagittarius

For Cancer’s Sign, as in the Goat he sways,

Resigns his first third Portion to His Rays:

For when he bears the Sun oppos’d in site,

His Day is equal to the Others Night:

This is the Reason why these Two combine,

And each hath the same Portion in each Sign.

His second part the Urn with watry Beams

O’re flows, and Pisces rules in the Extreams.

Here, Manilius says that the summer solstice holds the longest day and thus the shortest night, the winter solstice holds the longest night and thus the shortest day, and for this reason, the signs of Cancer and Capricorn must cede their first decan to the other’s sign.

Leo’s Decans: Aries, Taurus, Gemini

The Lion minds his Partner in the Trine,

And makes the Ram first Ruler in his Sign;

And then the Bull, with whom he makes a Square,

i’th’ Second Reigns; His Sextile Twins declare

Their Third pretence, and Rule the other share.

This is the first time he denotes that the aspects between signs can themselves serve as a justification for which decan is ruled by which sign, which helps us restore, later on, the decans of the sign he skipped (Sagittarius) and the sign he mislabeled (Pisces).

Virgo’s Decans: Cancer, Leo, Virgo

The Crab is chiefly Honour’d by the Maid,

The first place his, and there his Sway’s obey’d;

The next is Leo’s, and the last her own,

She Rules unenvy'd in her petty Throne.

This verse confused even the translators of the 1697 translation, as they marked this section as “In Cancer” before marking it out and writing “In Virgo” instead. Poetry, in any language, can be quite difficult to read, so it is not surprising that they first read this as Cancer’s decans rather than Virgo’s, especially since Manilius suddenly switched the order with which he explained the decans of the preceding signs. This is why close reading is so critical to historical method.

Libra’s Decans: Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius

The Ram’s Example Libra takes, and bears

A likeness in this Rule, as in the Years;

For as He in the Spring, her Scales do weigh

In Autumn equal Night with equal Day:

The first She rules her self, next Scorpio’s plac’t,

And Sagittarius Lords it o’er the last.

Manilius explains that Libra starts her own decans the way Aries starts his own decans because they are the two signs where night and day are considered equal at the two equinoxes. This is really intriguing when you consider what that means for the seasonal signs of Aries, Cancer, Libra, and Capricorn, and the way Manilius divides their decans. Aries and Libra both start their own decans because they mark the only seasons where the night and day are considered to be of equal length during their respective equinoxes. Cancer and Capricorn, however, take the other’s Sign as their first decan because they mark the two seasons where day and night are of unequal length during their respective solstices.

In essence, Manilius harmonizes the decans when he assigns Cancer and Capricorn to the first decan of the other’s Sign, because he allots the day of Cancer to Capricorn’s night and the night of Capricorn to Cancer’s day. Aries and Libra maintain their own decan because they are already in diurnal equilibrium.

Scorpio’s Decans: Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces

In Scorpio’s first Degrees the Goat presides,

Next Young Aquarius pours his flowing Tides;

Next Pisces Rules, for they in Waves delight,

The Flood pursue, and claim an easie-Right.

Manilius makes a critical error and skips Sagittarius’s decans, instead moving to Capricorn. This error causes him to mislabel Pisces’s decans as well. For Sagittarius, the correct decans are Aries, Taurus, Gemini.

Capricorn’s Decans: Cancer, Leo, Virgo

The grateful Goat doth Cancer’s Gift repay,

His First Third part resigning to his Ray;

i’th’ next the Lion shakes his flaming Mane,

The last feels modest Virgo’s gentle Rein.

Aquarius’s Decans: Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius

The Young Aquarius Libra’s Scales command,

Restrain his Youth, and check his turning Hand;

The next Ten parts Scorpio’s Rays enjoy,

Then Sagittarius Rules the giddy Boy.

Pisces’s Decans: Aries, Taurus, Pisces* (incorrect in text; corrected as Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces)

Pisces comes last, and sheds a watry flame

Its first Degrees resigning to the Ram;

The Bull’s the next, his own the last are found,

Content with the last Portion of the Round.

Because Manilius skipped Sagittarius, he assigns the wrong decans to the sign of Pisces, which is clear if you follow the order that he has ascribed to the decans of the Signs thus far. As, up until skipping Sagittarius, Manilius’s order of decans follows the zodiacal order itself.

Aries: Aries, Taurus, Gemini

Taurus: Cancer, Leo, Virgo

Gemini: Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius

Cancer: Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces

Leo: Aries, Taurus, Gemini

Virgo: Cancer, Leo, Virgo

Libra: Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius

Scorpio: Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces

Sagittarius: N/A*

Capricorn: Cancer, Leo, Virgo

Aquarius: Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius

Pisces: Aries, Taurus, Pisces??*

Notice how the zodiac literally repeats in order in the decans until he forgets to assign Sagittarius any decans at all, and, when he gets to Pisces, he skips the zodiac order that he has thus far followed. That means the last three decans of the zodiac, the ones ascribed to Pisces, cannot be Aries, Taurus, and Pisces because they negate the logic that he uses for every other sign.

As such, Pisces must hold the decans of Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces – not Aries, Taurus, and Pisces. This is definitely a mistake that others have caught and fixed, as the Manilius Decans that we are familiar with today have already been adjusted to account for this error in Manilius’s text. He himself says that “So intricate and puzzling are the Skies / not easie to be read by common Eyes” in the verse that prefaces his breakdown of the decans, so this oversight is easy enough to forgive.

This also means that Sagittarius must hold the decans of Aries, Taurus, and Gemini, as otherwise, the signs would not be found equally around the zodiac – and Manilius is very clear that every sign has an equal number of decans assigned to it. Additionally, if you trace the aspects between the signs, the decans assigned to each opposing pair form the same three aspects. Because Manilius used the terms contiguous and unequal for what we today call semi-sextile and inconjunct, I will use the terms he used for those particular aspects.

The six opposing pairs of the zodiac are Aries-Libra, Taurus-Scorpio, Gemini-Sagittarius, Cancer-Capricorn, Leo-Aquarius, and Virgo-Pisces.

The decans assigned to Aries belong to Aries, Taurus, and Gemini, which give Aries-Aries (conjunct), Aries-Taurus (contiguous), and Aries-Gemini (sextile). The decans assigned to Libra belong to Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius, which give Libra-Libra (conjunct), Libra-Scorpio (contiguous), and Libra-Sagittarius (sextile). The decans of both signs, then, hold the pattern of conjunct-contiguous-sextile.

The decans assigned to Taurus belong to Cancer, Leo, and Virgo, which give Taurus-Cancer (sextile), Taurus-Leo (square), and Taurus-Virgo (trine). The decans assigned to Scorpio belong to Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces, which give Scorpio-Capricorn (sextile), Scorpio-Aquarius (square), and Scorpio-Pisces (trine). So, the decans of both signs hold the pattern of sextile-square-trine.

The decans assigned to Gemini are Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius, which give Gemini-Libra (trine), Gemini-Scorpio (unequal), and Gemini-Sagittarius (oppose). Manilius erred by leaving out Sagittarius, but as mentioned previously, other astrologers have already correctly noted that the decans for Sagittarius should be Aries, Taurus, and Gemini. This is further strengthened by the fact that the aspect pattern matches that of Gemini, as Sagittarius-Aries creates a trine, Sagittarius-Taurus is unequal, and Sagittarius-Gemini are opposed. The decans of these two signs, then, hold the pattern of trine-unequal-oppose.

The decans assigned to Cancer are Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces, which give Cancer-Capricorn (oppose), Cancer-Aquarius (unequal), and Cancer-Pisces (trine). The decans assigned to Capricorn are Cancer, Leo, Virgo, which give Capricorn-Cancer (oppose), Capricorn-Leo (unequal), and Capricorn-Virgo (trine). This, then, gives the pattern of oppose-unequal-trine.

The decans assigned to Leo are Aries, Taurus, Gemini, which give Leo-Aries (trine), Leo-Taurus (square), and Leo-Gemini (sextile). The decans assigned to Aquarius are Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, which give Aquarius-Libra (trine), Aquarius-Scorpio (square), and Aquarius-Sagittarius (sextile). The decans of these two signs, then, hold the pattern of trine-square-sextile.

The decans assigned to Virgo are Cancer, Leo, Virgo. Manilius erred when he assigned Aries, Taurus, and Pisces to Pisces, and the corrections of other astrologers have noted that the proper decans for Pisces are Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces. This is further strengthened by the aspect pattern. For Virgo, the decans give the aspects of Virgo-Cancer (sextile), Virgo-Leo (contiguous), Virgo-Virgo (conjunct). The corrected decans of Pisces give Pisces-Capricorn (sextile), Pisces-Aquarius (contiguous), Pisces-Pisces (conjunct). The decans for these two signs, then, follow the pattern of sextile-contiguous-conjunct.

Thus, the aspect pattern of Aries-Libra is conjunct-contiguous-sextile, that of Taurus-Scorpio is sextile-square-trine, that of Gemini-Sagittarius is trine-unequal-oppose, that of Cancer-Capricorn is oppose-unequal-trine, that of Leo-Aquarius is trine-square-sextile, and that of Virgo-Pisces is sextile-contiguous-conjunct.

As a brief refresh, the aspects mentioned here are formed when they are a specific number of degrees apart: conjunct (0°), contiguous/semi-sextile* (30°), sextile (60°), square (90°), unequal/inconjunct*/quincunx* (150°), oppose (180°). Asterisks follow the modern names for these aspects.

No Love for Tradition

It actually takes reading through the first three books of Astronomica to piece together the full astrological microcosm Manilius was working from. He had no love for the Chaldeans, no loyalty to traditional methods, and no hesitation breaking from convention when he found it unwise. In Book III, he writes:

I know the Method the Chaldean Schools

Prescribe, but who can safely trust their Rules?

To each ascending Sign, to find their Powers,

They equal time allow, that equal time two hours.

…

But false the Rule; Oblique the Zodiack lies,

And Signs as near, or far remov’d in Skies,

Obliquely mount, or else directly rise.

He also chastised astrologers who viewed trines and squares by the number of signs between them without accounting for the degrees. He was especially scathing towards astrologers who visually identified trines and squares rather than mathematically. In Book II:

But now should any think their Skill designs

The Squares aright, and well describes the Trines,

And that they hit the Rule when e’re they give

Four Signs to Squares, to Trines allotting Five;

.And thence presume to guess what mutual Aid

The Signs afford, they’ll find their Work betray’d:

For though on every side five Signs are found

To make the several Trines that fill the Round,

Yet Births in each Fifth Sign no Fates design

To share th’united Influence of the Trine.

They lose the Thing though they preserve the Name,

For Place and Number still oppose their Claim.

Manilius is saying that just because two planets are five signs apart doesn’t mean they form a real trine. Unless the planets are actually 120° apart, the connection is false. The same goes for squares, which must hit exactly 90° to function. In Book II:

Then take Advice, nor from my Rules depart,

Nor think thy Figures well design’d by Art,

‘Cause Four in Squares, Three equal Lines in Trines

In Angles meeting there divide the Signs;

For in all Trines the single sides require

Sixscore [120] Degrees to make the Scheme entire.

Squares ninety ask: but more or less proclaim

The Figure faulty, and destroy the Frame.

Manilius would not agree with the practice today of applying orbs to either squares or trines, as he was very adamant that you cannot create a square without 90° angles or a trine (triangle) without a total of 120° – which is mathematically and geometrically accurate. So, Manilius was actually more precise than Ptolemy was in defining when trines and squares appear in charts. For Manilius, a single degree more or less than 120° disrupts the trine, a single degree more or less than 90° disrupts the square, and a disrupted trine or square shows a dissonance in a chart where harmony between the signs failed to fully form. There’s a lot packed into that implication that bears further consideration.

Today, however, I am focused on demonstrating how Manilius subdivided the zodiac – first by the 12 Signs, then by the 36 decans, then the 144 dodecatemoria, and finally the 720 stadia. This is the most mathematically precise rendering of ancient astrology that we may possess, but it has largely been ignored because Manilius wrote his astrological treatise in verse.

Next Up: I’ll explore what Manilius reveals about the practice of casting horoscopes in 1st century Rome and what it means that he viewed the zodiac as oblique.

©The Knotty Occultist 2020-2025