Manilian Quadrant Astrology: Where the Oblique Zodiac Meets the Geography of Earth

Manilius used the real geography of the Earth to geometrically define the quadrant system he used in his astrological practice. He calculated rising signs by degrees rather than adhering to the Chaldean method of assigning two hours to each rising sign. Manilius rejected Equal House divisions, ignored Whole Sign conventions, and mapped the zodiac belt using the polar and tropical boundaries of the Earth. The dominant narrative of astrology’s history erases Manilius, but his own writings demand that story be revised. He used quadrants and unequal houses over 1,500 years before Placidus, proving that astrologers before Ptolemy did, in fact, use unequal houses.

Zora Lysara

6/24/202529 min read

All excerpts come from the 1697 English Text The Five Books of Manilius which is freely accessible via the Internet Archive. The English text is a translation of Manilius’s Astronomica, which was written sometime in the 1st century CE, predating Ptolemy by 100 years or more.

The Curated Nature of History

History is curated. Even facts are filtered, shaped by the stories that survive. What we call “truth” is often only half the story. What few realize is that some facts are purposefully buried, stories hidden, truths lost. Societies choose what facts they carry forward, and scholars often reinforce that selection. For historians, this makes recovering the past a difficult task: we are always working from fragments, always chasing ghosts.

The half of the story we’re told about quadrant-based astrology is that it began in the 17th century, when Placidus introduced his system, where he divided houses unequally using diurnal arcs and complicated mathematical equations that, today, are easily handled by computer software.

This is the story that is continually carried forward by both traditional and modern astrologers, as each group has a vested interest in perpetuating that particular narrative. For traditional astrologers, who swear by Whole Sign or Equal House systems, the very idea that Placidus wasn’t the first to map unequal quadrants is anathema. For modern astrologers, who often swear by Placidus, the idea that his quadrant system is not the oldest version nor as mathematically elegant as it seems is sacrilege (even though Placidus gave the credit for the system to someone else).

Vested interests in a story–told a particular way, through a particular lens–ensure that history carries forward narratives that may not actually hold historical truth. Because the stories we tell about the past are not the same as the truths it holds. Facts are curated, and the stories that don’t serve the interests of a group are often ignored or laid aside.

Unfortunately for both camps–modern and traditional astrologers alike–my vested interest as a historian is restoring the knowledge of those whose stories were intentionally suppressed, whose voices were silenced.

And, today, I am restoring the voice of Manilius, an astrologer, geometer, and poet who lived in 1st century CE Rome. Because he mapped the sky in quadrants, described unequal houses, and did it 1,500 years before Placidus ever touched a chart. And, unfortunately for Placidus, Manilius’s division of the zodiac into quadrants is extremely elegant. Because, unlike Placidus, Manilius divided the quadrants using geographical precision rather than abstract mathematics.

The Quadrants of Manilius

Manilius used the geography of the Earth to divide the zodiac into quadrants, and he used the five “imaginary” circles most of us learn about in school to make those divisions. Those five circles are the Tropic of Cancer, the Tropic of Capricorn, the Equator, the Northern Arctic Circle, and the Southern Arctic Circle.

While these are "imaginary" lines–meaning they are not physically visible–they’re foundational to geography and astronomy. We still use them today to determine critical information about position and motion on the planet. The Equator marks the Earth’s zero point for latitude, while the Tropics define the boundaries of the Sun's apparent motion north and south across the year. The Arctic and Antarctic Circles mark the polar extremes, beyond which there are periods of 24-hour daylight or darkness.

In Book I of Astronomica, Manilius defines the polar axis:

The World’s Diameter by Art is found,

Almost the third Division of the Round.

Therefore as far as four bright Signs comprize,

The distant Zenith from the Nadir lies.

And two thirds more almost surround the Pole,

The Twelve Signs measure, and complete the Whole.

In this verse, Manilius is describing the vertical axis of the Earth–the polar axis–which runs from the Zenith (celestial north) to the Nadir (celestial south). In modern terms, this is the same axis around which the Earth rotates. While today we use the prime meridian and parallels of longitude for global positioning, the rotational axis is the fundamental basis for both celestial north/south and the mapping of Earth's hemispheres.

In astrology, the zenith (topmost) of a chart is the Midheaven while the nadir (bottommost) of a chart is the imum coeli, or I.C. By mapping the polar axis of the Earth, Manilius is already telling us that the core vertical axis of an astrology chart is a microcosmic reflection of the Earth’s polar axis.

Manilius continues, in Book I:

Thus far advanc’t my towering Muse must rise,

And sing the Circles that confine the Skies,

Describe the track, and mark the shining Way,

Where Planets Err, and Phoebus bears the Day.

Manilius tells us point-blank that the circles define the structure of the sky: “the circles that confine the skies.” He is stating explicitly that the geometry of heaven is built on invisible bands–tropics, equator, ecliptic, and polar circles. The line “where planets err” uses an older sense of “err,” meaning to wander or to move unpredictably, referring to the motion of the planets. And “Phoebus bears the day” is a classical allusion to the Sun (Phoebus Apollo), whose daily motion across the sky was understood, in the geocentric model, as circling Earth.

He continues, in Book I:

One towards the North sustains the Shining Bear,

And lies divided from the Polar Star;

Exactly six divisions of the Sphere.

Manilius is describing the Northern Arctic Circle–the northernmost of the five major circles of latitude. “The Shining Bear” refers to Ursa Major, a key circumpolar constellation visible year-round from northern latitudes. The line “lies divided from the Polar Star” positions this circle as proximate but not identical to the celestial pole (which hosts Polaris). The “six divisions of the sphere” refers to six zodiac signs: from the perspective of the Northern Arctic Circle, only half the zodiac is ever visible above the horizon at any one time. This is an early acknowledgment of unequal visibility–a foundational principle of unequal house systems–and it demonstrates that Manilius is treating the zodiac as obliquely tilted against the Earth’s rotational axis.

Manilius continues, in Book I:

Another drawn through Cancer’s Claws confines,

The utmost Limits of the Fatal Signs;

There when the Sun ascends his greatest height

In largest Rounds He whirls the lazy Night.

Pleas’d with his Station there He seems to stay,

And neither lengthens nor contracts the Day.

The Summer’s Tropick call’d. ——

It lies the fiery Sun’s remotest Bound,

Just five Divisions from the other Round.

The circle that Manilius introduces here is the Tropic of Cancer, which is made clear in the lines “drawn through Cancer’s claws” and “the summer tropick call’d.” The Tropic of Cancer is the northenmost boundary of the Sun’s apparent path through the sky. During the Summer Solstice, the Tropic of Cancer marks the highest point of the solar arc, and the Sun appears almost stationary in the sky. The Summer Solstice marks the longest day and shortest night of the year, and that day is longest along the Tropic of Cancer.

When he says “five divisions from the other round,” Manilius is describing a span of six signs. This is a geometric distinction that requires close attention: to contain six signs between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, five divisions must be made. On a blank astrology chart, this becomes visibly clear–there are exactly five dividing lines between the chart’s zenith and nadir.

Manilius continues, in Book I:

A third twines round, and in the midst divides

The Sphere, and see the Pole on both its sides.

And there when Phoebus drives, He spreads his Light,

On All alike, and equals Day and Night.

For in the midst, He doth the Skies divide,

And chears the Spring, and warms the Autumn’s Pride.

And this large Circle drawn from Cancer’s Flame,

Just four Divisions parts the Starry Frame.

Manilius describes the equator in these two verses and also tells us, for the first time, that the “starry frame” – or astrology chart – is divided into four quadrants. The equator is the central point of the chart, with the north and south pole represented as the northernmost and southernmost points of the chart.

When Manilius tells us that the equator divides the sky by “cheering the Spring” and “warming Autumn’s Pride,” he is telling us that Aries sits at the eastmost point and Libra at the westmost point. In order to know this, however, you have to understand that Aries is the zodiac sign that marks the vernal equinox and Libra the sign that marks the autumnal equinox.

Manilius continues, in Book I:

Another Southward drawn exactly sets

The Utmost Limits to the Sun’s retreats;

When hoary Winter calls his Beams away,

Obliquely warms us with a feeble Ray,

And whirls in narrow Rounds the freezing Day.

To Us his Journey’s short, but where He stands

With Rays direct, He burns the barren Sands.

To wisht-for Night he scarce resigns the Day,

But in vast Heats extends his hated Sway.

Manilius introduces the Tropic of Capricorn here and simultaneously tells us that the summer and winter solstice are oppositely marked by the tropics depending on the hemisphere. We know this is the Tropic of Capricorn because of the line, “the utmost limit to the Sun’s retreat,” and, since Rome is the northern hemisphere, that means Tropic of Capricorn. Because the Tropic of Capricorn marks the winter solstice, the day of the year in which the day is shortest and the night longest.

What tells us that Manilius understood that the Tropics operated in reverse order with the solstices comes from the lines, “To us his journey’s short, but where he stands / with rays direct, he burns the barren sands.” In this context, “us” refers to those residing in the northern hemisphere. When the night is at its longest in the northern hemisphere, it is at its shortest in the southern hemisphere. This is a natural consequence of the spherical nature of the Earth.

He continues, in Book I:

The last drawn round the Southern point confines

Those Bears, and lies the Utmost of the Lines.

Wise Nature constant in her Work is found:

As five Divisions part the Northern Round;

From the North point, This Southern Round appears

Just five Divisions distant from its Bears.

The fifth of the “imaginary” circles that Manilius introduces is the Southern Arctic Circle, otherwise known as the Antartic Circle. He also tells us here that the northern constellations, specifically Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, are not visible from the South Pole. As before, Manilius tells us that the Antartic Cirlce is “five divisions” away from its counterpart. Geometrically, there are five dividing lines between the eastmost and westmost points of the zodiac.

So far, Manilius has told us that the Arctic and Anarctic Circles are five divisions away from each other, that the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn are five divisions away from each other, that the equator is the central point of the chart, and that there are four divisions of the “starry frame.” Using these five circles, Manilius divides the chart into four quadrants.

It is in the next verse of Book I, however, that Manilius makes it clear that he is using quadrants:

Thus Heaven’s divided, and from Pole to Pole

Four Quadrants are the Measure of the Whole.

The Circles five, by these are justly shown,

The Frigid, Temperate, and the Torrid Zone.

All these move Parallel, they set, they rise,

At equal Distance moving with the Skies;

Turn’d with the Orbs the common Whirl repeat,

Are fixt, nor vary their allotted Seat.

Manilius specifically names quadrants, claiming that “four quadrants are the measure of the whole.” He also tells us, plainly, that the five circles he has just outlined are used to define the quadrants. In addition, Manilius explains that the five circles define the frigid, temperate, and torrid zones. These are names that we still use today for different geographical zones. The frigid zones are those near the poles, the temperate zones are those between the poles and the tropics, and the torrid zones are the tropics themselves.

A common misreading of this passage is to assume that the line “at equal distance moving with the skies…are fixt, nor vary their allotted seat” refers to the zodiac signs or houses. But Manilius is not talking about signs or houses–he is talking about the five circles themselves. These circles–Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, Equator, Arctic Circle, and Antarctic Circle–are imaginary lines based on Earth’s geometry. They never move. They remain constant no matter the time or date, and serve as the fixed reference points by which the motion of the heavens is measured.

To make his quadrant division even clearer, Manilius continues, in Book I:

From Pole all round to Pole two Lines exprest,

Adversely drawn, which intersect the rest

And one another; They surround the Whole,

And crossing make right Angles at each Pole:

These into four just parts, by Signs, the Sphere

Divide, and mark the Seasons of the Year.

Manilius explicitly states that the sphere–by which he means the zodiac wheel itself–is split along two axes: the north-south and the east-west axes. Where these axes meet, they form right angles and divide the zodiac wheel into four quadrants that are seasonally defined.

While Manilius had already explained how the five circles delineate the quadrants, he reiterates here that these circles intersect the polar axis (running north to south) and converge at the equator, dividing the zodiac into four distinct quadrants that correspond to the four seasons.

The quadrant between the eastern axis and northern axiss runs from Aries to Cancer, marking the spring season. The quadrant between the northern axis and western axis runs from Cancer to Libra, marking the summer season. The quadrant between the western axis and southern axis runs from Libra to Capricorn, marking the autumnal season. The quadrant between the southern axis and the eastern axis runs from Capricorn to Aries, marking the winter season.

The Meridians and the Horizon

After Manilius finishes describing the immovable circles, he moves on to a discussion of the movable circles of the meridians and the horizon. In Book I, he continues:

Two more are movable: one from the Bear

Describ’d surrounds the middle of the Sphere,

Divides the Day, and marks exactly Noon

Betwixt the rising and the setting Sun:

This is the Prime Meridian that runs from the north to the south pole, as it is the zenith of the chart that marks high noon and the nadir that marks midnight. The meridian is “movable” because, from an observer’s perspective, it shifts across the sky as a consequence of the Earth’s rotation.

Manilius continues the description of meridians in Book I:

The Signs it changes as we move below,

Run East or West, it varies as You go;

For ’tis that Line, which way foe’er we tread,

That cuts the Heaven exactly o’er our head.

And marks the Vertex; which doth plainly prove

That it must change as often as we move.

Not one Meridian can the World suffice,

It passes through each portion of the Skies.

Although meridians run in a north–south orientation, they are distributed east to west across the Earth’s surface, and it is this longitudinal variation that determines how the signs overhead shift as one travels. These are the lines we now use to calculate longitude, and they form the backbone of global mapping.

What this tells us is that Manilius was extremely well-educated, as he was using the system of latitude, longitude, and meridians that was originally proposed by Eratosthenes in the 3rd Century BCE.

This is actually critical information because Ptolemy is often credited with formalizing the system of using the prime meridian as a mapping system, but Manilius was already doing that over 100 years before Ptolemy was even born. Because Ptolemy’s work is often viewed as the primary canonical text for classical astrologers, Manilius’s older – and more elegant system – gets ignored in favor of Ptolemaic astrology.

Manilius concludes the section on the meridians in Book I:

Thus when the Sun is dawning o’er the East

’Tis their sixth hour, and sets their sixth at West:

Though those two hours we count our days extremes,

Which feebly warm us with their distant Beams.

Manilius tells us here that solar time shifts with longitude. When it is 6am (sunrise) along one meridian, it is 6ppm (sunset) along the meridian on the opposite side of the Earth. This early articulation of relative time predates the formal invention of time zones by nearly two millennia and shows that Manilius understood that the Sun's position in the sky – and thus the hour of the day – depends on geographic location.

Next, Manilius turns, in Book I, to describing the horizon:

To find the other Line cast round thine Eyes,

And where the Earth’s high surface joys the Skies,

Where Stars first set, and first begin to shine,

There draw the fancy’d Image of this Line:

Which way foe’er you move ’twill still be new,

Another Circle opening to the view;

For now this half, and now that half of Sky

It shews, its Bounds still varying with the Eye.

This Round’s Terrestrial, for its bounds contain

That Globe, and cut the middle with a Plain;

’Tis call’d the Horizon, the Round’s design,

(For ’tis to bound) gives title to the Line.

The horizon, which comes from the Greek phrase horizōn kyklos meaning “bounding circle,” is the visible boundary that seems to separate the Earth’s surface from the skies above it. Uniquely, the horizon itself depends on the observer’s position on the Earth. Importantly, it is the horizon that moves with the viewer, which also means the skies look different everywhere on Earth. As the horizon moves, so too does the view of the sky shift.

In astrology, the horizon defines the Ascendant (rising sign) and Descendant (setting sign), and these two points determine the central axis of a person’s chart. Manilius’s description makes clear that these cardinal points are intimately tied to geography and the viewer’s perspective. In other words, Manilius shows us here that the Ascendant cannot be identified without first identifying which local horizon is intersecting the zodiac from the perspective of the chart holder. Basically, this is the reason that a person’s city of birth must be known in order to determine their Ascendant.

After Manilius finishes describing the meridians and the horizon, he turns to the ecliptic itself, which is oblique. In Book I, he writes:

Two more Oblique, and which in adverse Lines

Surround the Globe, Observe: One bears the Signs

Where Phoebus drives and guides his fiery Horse,

And varying Luna follows in her Course.

Where Planets err as Nature leads the Dance,

Keep various measures undisturb’d by Chance;

Its highest Arch with Cancer’s beams do glow,

Whilst Caper lies, and freezes in the low:

Twice it divides the Equinoctial line,

Where fleecy Aries, and where Libra shine.

Three Lines compose it, and th’ Eclyptick’s found

Ith’ midst; and all decline into a Round.

Nor is it hid, nor is it hard to find,

Like others open onely to the Mind;

For like a Belt with studs of Stars the Skies

It girds and graces; and invites the Eyes:

To twelve Degrees its Breadth, to thrice sixscore

Its Length extends, and comprehends no more:

Within these bounds the wandering Planets rove,

Make Seasons here, and settle Fate above.

The ecliptic forms a slanted circle around the Earth, tilted relative to the equator, and it traces its oblique path through the 12 zodiac signs. It crosses the equinoctial line twice, at Aries and Libra, where it marks the spring and autumn equinoxes.

From Aries to Libra, the Sun appears to ascend the northern arc of the ecliptic, reaching its peak at Cancer. From Libra to Aries, it descends through the southern arc, reaching its lowest point at Capricorn. In this way, the signs of the zodiac are bound between the solstices (Cancer and Capricorn) on the north–south axis and the equinoxes (Aries and Libra) on the east–west axis, forming the tilted ring of the ecliptic.

Critically, Manilius also explains that the ecliptic is “twelve degrees in breadth,” meaning that he was allowing an orb of 6° for planetary drift in either declination or celestial latitude. Today, the IAU (International Astronomical Union) allows an orb of 8° for planetary drift in either direction.

Like many other ancient astrologers, Manilius had already accounted for the drift. Incidentally, this is why all serious astrologers reject the theory of the “13th sign”: the ecliptic is a belt with breadth; it shifts over time, and the drift was accounted for centuries ago.

After explaining the ecliptic, Manilius turns to the second oblique path in the heavens: the Milky Way. He recounts a series of myths and speculative explanations for its origin, offering a surprisingly thorough account of the competing theories about the galaxy’s nature circulating in 1st century CE Rome.

The Rising and Setting Stadia of the Zodiac

However, since my focus is on Manilius and his quadrant-based astrology, I am going to shift from the passages of Book I and move to Book III of Astronomica, where he lays out a remarkably precise system for calculating the amount of time each of the 12 signs takes to rise.

Manilius rejected both what we call Whole Sign and Equal House today, as he was mapping the rising of each of the 12 signs by stadia (half-degree increments) and was plainly contemptuous towards the Chaldeans, who assigned 2 hours to each sign.

This is the half of the story that gets surreal because, as I mentioned at the beginning of this article, what we have been taught is that Placidus invented a quadrant system using diurnal arcs to map the time it takes each sign to rise in the 17th century. However, what has been missed is the fact that Manilius was mapping rising signs by stadia over 1500 years before Placidus ever set eyes upon an astrology chart.

Now, it’s critical to note that Placidus himself never claimed to have invented the system that bears his name. He explicitly attributed it to the 12th-century Hebrew astrologer Abraham ibn Ezra, who, in turn, claimed that Ptolemy had outlined the quadrant system in the Tetrabiblos.

However, modern Hellenistic revivalists–especially Chris Brennan–have argued that Ptolemy used Whole Sign houses, and that all Hellenic astrologers did the same. This is where things start to get messy.

Because Manilius, particularly in Book III of Astronomica, provides a powerful counterargument. He uses stadia (half-degree units) to calculate how long each sign takes to rise and set. He demonstrates how these values vary by latitude, factoring in geography and season. This is not Whole Sign nor is it Equal House. It is a time-based quadrant system over 1500 years before Placidus, functioning with more astronomical precision than most systems in use today.

To claim that Whole Sign was the only house system used by Hellenic astrologers is a blatant omission of evidence, one that conveniently serves a particular historical narrative. And remember what I said earlier: everyone has vested interests. That includes scholars. Academic history is full of cases where scholars have been ruined because their evidence was cherry-picked, ignored, or outright fabricated to support theories that only held when no one checked their work too closely.

In Book III, Manilius writes:

I know the Method, the Chaldean Schools

Prescribe, but who can safely trust their Rules?

To each ascending Sign, to find their Powers,

They equal time allow, that time two Hours:

And from that Degree, from which the Sun

Begins to start, his daily Course to run,

Two Hours to each succeeding Sign they give,

Still thus allowing, ‘till their search arrive

At the Degree and Sign they seek for where

The Number ends, the Horoscope is there.

The method Manilius is describing in this verse is the Chaldean method of finding the horoscope – in other words, determining the ascendant around which the rest of the chart revolves. Manilius continues:

Manilius is very clear here that every sign should not be given the same amount of time in the sky nor an equal space in the houses. He does this by explaining that, seasonally, the length of days and nights vary. The Signs cannot be given the same amount of time to rise because that is illogical based on a simple observation of the seasons.

He is arguing here, in 1st century CE Rome, over 1500 years before Placidus became the standard house system used by modern astrologers, that the Signs are unequal and that houses need to reflect the truth of how much time each Sign takes to set and rise. Manilius is explicitly denouncing the Chaldean method of assigning two hours per sign; he is denouncing the practice of Equal Houses, the practice of Whole Sign. And he is doing this over a century before Ptolemy standardized Hellenic astrology, 11 centuries before Abraham ibn Ezra wrote his treatise on Ptolemy, and 16 centuries before Placidus borrowed from Ezra.

This is significant because it undermines the argument that many Hellenic revivalists make that Whole Sign was the only house system in use in ancient times. Manilius tells us otherwise. He was clearly not using Whole Sign, and to discount his method simply because it “doesn’t match” the other sources from the time period is gross scholarly negligence. That is not how legitimate scholarly work is done.

All primary sources are considered relevant to a time period. Historical sources aren’t like statistics, where you can just toss out outliers in a data set like they are anomalies. Outliers in data sets only occur when you have a full set of data and there are outliers in that full set. In history, we never have the full set of data. Outliers aren’t applicable to historical sources. There is no such thing as an anomalous historical source. All historical sources are valid for their time period. To claim otherwise is to deny the reality that we do not have the full set of sources.

So, Manilius may be one of the only sources we have from a 1st century CE Rome astrologer practicing with an unequal house system, but that doesn’t mean he was the only one practicing that way. To assume that is to misunderstand how historians track sources. If there is a single source from a time period that denotes a particular method, it is a given that someone else was practicing the same method. Especially in a time period when only high officials were even literate, let alone published.

Any book that has survived into the present day from 1st century CE Rome was widely circulated during that time period because all books that circulated in that time period were transcribed by hand. People did not waste time copying material by hand that they felt was unimportant, anomalous, or somehow outside of the norms of the time. However obscure Manilius may seem today, he clearly mattered more than we know, and we know that because we still have his words today.

We also know that he was seen as important at least up through the 17th century, as his five books of epic poetry were translated into other languages during the Enlightenment period. People do not pay for translations of works they see as anomalous or as holding little value, and that was especially true during the Enlightenment period. Every text that was translated, published, and circulated during that period in European history was viewed as a valuable intellectual contribution to societal progress. We don’t necessarily know how people of that time period received Manilius’s works, but we do know that they considered his work important enough to translate. And, in that era, translation was an endorsement.

So, the method Manilius is describing in Book III of Astronomica is not an anomaly or an outlier of astrological practice in 1st century CE Rome. It is a method that we know was practiced simply because his works were transcribed and the knowledge survived. Just because it “doesn’t match” the other surviving works from that time period doesn’t make it an anomaly; the only “anomalous” thing about the text is that it is the only remaining one that describes an alternative practice to Whole Sign/Equal House practiced during that time period. Which Manilius continues to outline, in detail, in Book III:

But false the Rule; Oblique the Zodiack lies,

And Signs as near, or far remov’d in Skies,

Obliquely mount, or else directly rise:

In Cancer, for immense his Round, the Ray

Long continues, and slowly ends the Day;

Whilst Winter’s Caper in a shorter Track

Soon wheels it round, and hardly brings it back.

Aries and Libra, equal Day with Night,

Thus middle Signs to the Extreams are opposite.

And signs Extream too, vary in their Light.

Nor are the Nights less various than the Days

Equal their measure, only Darkness sways,

In Signs adverse to those that bore the Rays:

Then who can think when Days and Nights are found,

In length so differing thro’ the Yearly Round,

There should be given to every Sign in Skies,

An equal Space, an equal Time to rise?

But more than this: The Hours no certain space

Of time contain, but vary with the Days:

Yet every Day in what e’re Sign begun,

Beholds six Signs above the Horizon,

Leaves six below; and therefore Rules despise,

Because the Hours no equal time comprise,

Which give two Hours to every Sign to rise.

The Hours in number Twelve divide the Day,

And yet the Sun with an unequal Ray

Now makes a shorter, now a longer stay.

Manilius tells us, in no uncertain terms, that the hours are unequal in length, that there are 12 hours (i.e. 12 houses), and that there are always six signs above and below the horizon. Manilius claims that the Signs “despise the Rules” that give two hours to each Sign because that isn’t how the Sun travels through the sky.

It is the next part of Manilius that is most often misunderstood as him describing equal houses – he is not. I’ll explain why, after giving you the verse from Book III:

Nay farther, tho’ you many ways pursue

To find their length you’ll never meet the true,

But thus: Take all that space of time the Sun

Meets out, when every daily Round is Run,

Let equal Portions next that time divide;

And then these Portions orderly apply’d

To Days, will shew their length, from thence appears

Their varying Measures through the rouling Years.

The Standard this, by which our Art Essays

Winter’s slow Nights, and tries the Summer’s Days.

This must be fixt, when from the’ Autumnal Scales,

The Day declines, and Winter’s Night prevails:

Or in the Ram whence Winter’s Nights retire

The Hours restoring to the Summer’s Fire:

In those two Points the Day and Night contain

Twelve equal Hours. For with an even rein

The Sun then guides, and whilst his Care doth roul

Thro’ Heaven’s midd Line, he leans to neither Pole:

But when remov’d, he to the South declines,

And in the Eighth Degree of Caper shines,

The Winter’s hasty Day moves nimbly on,

Nine Hours and half; so soon the Light is gone.

But Night drives slowly in her gloomy Carr,

Takes fourteen Hours and half for her unequal share;

Thus twice twelve Hours in Day and Night are found,

To fill the natural Measure of the daily Round.

Then Light increases still, as Nights decay,

‘Till Cancer meets her in the Fiery way,

And sets sure bounds to her encroaching sway.

Then turns the Scene, and Summer’s day descends

Thro’ Winter’s Hours, still losing as it bends:

And then the Days of equal length appear,

With Nights ‘th’adverse Season of the Year,

And Nights with Days: For by the same Degrees

That once they lengthened, now the Times decrease.

Now learn what Stadia, learn what time in Skies

Signs ask to Sett, and what they claim to Rise:

Observe, short rules my Muse, but full she brings,

And Words roul from Her, crowded up with Things.

For Aries, Prince of all the Signs comprise

Full forty Stadia, for his time to rise,

But Eighty give him when He leaves the Skies:

One Hour, and one third part his rise compleats,

This space of time, He doubles when He sets.

The following Signs to Libra rising, claim

Eight Stadia more, and Setting lose the same.

And thus in order following Signs require

Still sixteen Minutes more to raise their Fire,

And lose as much, when setting they retire.

Thus signs to Libra, as they rise increase;

And thus they lose when they descend to Seas:

For all the Signs that do from Libra range,

Take equal measures, but the Order change;

For signs adverse to equal times engross,

But setting Gain, and still arise with loss.

Thus Hours and Stadia which bright Aries gets

When rising, Libra loseth when she sets;

And all the time, which when He leaves the Skies,

The Ram possesses, Libra takes to rise:

By this Example, all the rest define,

The following imitate the Leading Sign.

Manilius is not arguing here for the use of Whole Sign or Equal House but instead telling us that it is only at the Spring and Autumn Equinoxes that days and nights are in exact equilibrium with one another. He is essentially telling us that the backbone of the astrology chart itself rests on the equilibrium of day and night.

He even tells us that when the Sun is not at the point of its arc that marks the equinoxes that it declines to the south, marking longer nights, as the year moves towards the winter solstice. And, though he doesn’t state it directly, he implies that the Sun declines towards the north as the year moves towards the summer solstice. He tells us that days and nights increase/decrease in hours in a parallel incline/decline as the year moves from the full equilibrium of the equinoxes and towards the unequal nature of the summer and winter solstices.

What makes it even clearer that Manilius is not using an equal division of the houses is the next verse of Book III, where he gives specific stadia for the rising and setting of each of the twelve signs:

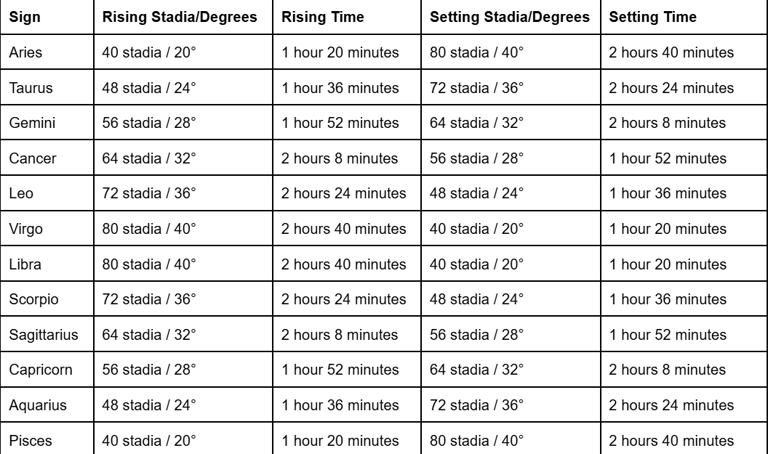

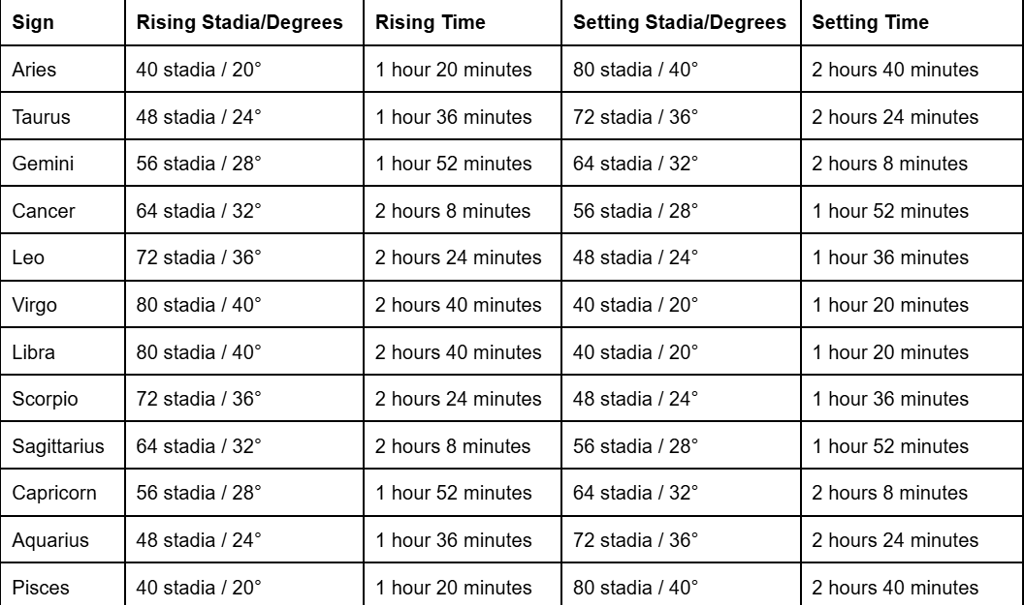

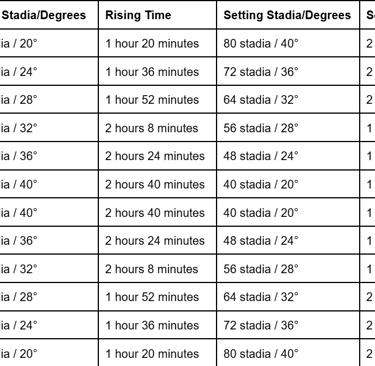

Manilius reveals, in stunningly precise detail, exactly how much time he allotted to each of the 12 signs for rising and setting via stadia, or half-degree increments. Aries, for instance, assigned 40 stadia to rise, he assigned 80 to set. This ratio increases incrementally by eight stadia in both rising and setting times to each sign.

Here, Manilius is saying that the signs from Aries to Libra have rising and setting stadia that mirror the rising and setting stadia of the signs from Libra to Aries. When stadia are translated into time increments (with a stadia being 0.5° and 1°=4 minutes), we get the following:

Incredibly, Manilius was rejecting the concept of Whole Sign and Equal House as early as the 1st century CE. He did not assign the standard two hours per sign that the Chalden schools taught, choosing instead to base his method on the actual path the Sun appeared to make through the sky and the seasonal impact that lengthened/shortened days and nights.

Manilius continues, in Book III:

Thus you may find the Horoscope in Skies,

And tho’ Oblique the Circling Zodiack lies,

This Point determin’d, you may fix them all,

What Crowns the Top, and what supports the Ball:

The Signs true Setting, and true Rising trace,

Assign to each their proper Powers and Place,

And thus what stubborn Nature’s Laws deny,

Our Art shall force, and fix the rowling Skie.

Nor is o’re all the Earth, the length of Night,

And Day the same; they vary with the sight;

Nor, would the Ram alone and Scales agree,

In Day and Night; in every Sign would be

The Equinox, if as these Rules devise,

Two Hours were given to every Sign to rise.

Manilius says that it is absolutely absurd to assign an equal place, an equal space, to every sign of the zodiac, because to do so would mean that every sign marked an equinox. The tropical zodiac is, itself, based on seasonal logic, so Manilius is calling out the Chaldeans for using absurd logic by dividing the houses as if the zodiac sits in perpetual equilibrium throughout the year the way it does during the Spring and Autumn Equinoxes.

Manilius continues, in Book III:

In that Position which Directs the Sphere,

And in the Horizon both Poles appear;

The Day maintains an equal length to Night,

And that Usurps not the others Right:

No Inequality in Skies is found,

But equal Day, and equal Night goes Round.

Manilius is telling us that the horizon – the line that visibly divides the earth from the sky, and, in a chart, divides night from day, is always equal in size. He is referring back to his earlier claim that there are always 6 signs found above the horizon and 6 signs found below. Critically, he is not claiming here that the houses are equal. He is saying that the horizon of the horoscope, the one that divides the northern and southen hemispheres of an astrology chart, is always horizontally placed between the eastern (rising) and western (setting) points of the chart. The sky is split evenly into day and night by position, but the movement of the signs through that horizon is deeply unequal.

Manilius continues, in Book III:

Those Days and Nights which Spring and Autumn bear,

They see unvary’d thro’ the rowling Year,

Because the circling Sun in every Sign

Runs round, and measures still an equal Line;

Whether thro’ Cancer’s height he bears the Day,

Or thro’ the Goat oppos’d He bends his way,

The Day’s alike, nor do the Nights decay

For tho’ Oblique the Zodiack Circle lies,

Yet all the Zones do at right Angles rise

Still Parallel, and whilst the Sphere is Right

Half Heaven is Hid, and half expos’d to sight.

Manilius is specifically describing how the equinoxes see equal days and nights, so the signs equally rise and set. It would be a critical error to interpret this as Manilius supporting Whole Sign or Equal House, considering he just finished criticizing that method with a large degree of disdain.

He continues, in Book III:

Hence take thy way, and o’re Earth’s mighty Bend

From this midst Region move to either End,

As weary Steps convey thee up the Ball

By Nature rounded and hung midst the All

To either Pole, whilst you your way pursue

Some parts withdraw, and others rise to view.

To you thus mounting as the Earth doth rise

So varies the Position of the Skies,

And all the Signs that rose Direct before

Obliquely mount, and keep the Site no more;

Oblique the Zodiack grows, for whilst we range,

Tho fixt its place, yet ours we freely change;

Tis therefore plain that here the Days must prove

Of different Lengths, since Signs obliquely move,

Some nearer roul, whilst some remoter rove,

And measure still unequal Rounds above.

Manilius is saying, quite plainly, that the Signs comprise different rising and setting times at different geographical locations. As you move away from the Equator, towards either Pole, the way that the Signs set and rise vary in time despite being fixed in space. The Signs themselves never move, of course; instead, we move across the planet. And, as we move, the Signs seem to set and rise at different intervals and are viewed differently from every local horizon. Manilius is making a profoundly geographical argument.

Manilius continues, in Book III:

As nearer to the Arctick Round you go

The Hours increase, and Day appears to grow;

The Summer Signs in ample Arch invade

Our Sight, the Winter lie immerst in Shade;

The more you Northward move, the more your Eyes

Their Lustre lose; they set as soon as rise:

But pass this Round, as you your way pursue,

Each Sign withdraws with all its parts from view,

Then Darkness comes, and chases Light away,

And thirty Nights excludes the Dawn of Day:

Thus by degrees Day wasts, Signs cease to rise.

For bellying Earth still rising up denies

Their Light a Passage, and confines our Eyes.

Continued Nights, continued Days appear,

And Months no more fill up the rouling Year.

Manilius tells us explicitly that the closer to the poles you move, the way the sky looks changes. He is describing circumpolar reality - how days and nights are almost perpetual for a significant length of time - and explains that there are Signs that never rise during certain parts of the year. This becomes even clearer as he continues, in Book III:

Should Nature place us where the Northern Skies

Creak round the Pole, and grind the propping Ice:

Midst Snows eternal, where th’ impending Bear

Congeal’d leans forward on the frozen Air;

The World would seem, if we survey’d the whole

Erect, and standing on the nether Pole.

Its sides, as when a Top spins round, incline

Nor here nor there, but keep an even Line,

And there Six Signs of Twelve would fill the sight

And never setting at an equal Hight,

Wheel with the Heavens, and spread a constant Light.

And whilst thro’ those the Sun directs his way

For long Six Months with a continued Ray

He chances Darkness, and extends the Day.

But when the Sun below the Line descends

With full Career, and to the lower bends,

Then one long Night continued Darkness joins,

And whilst he wanders thro’ the Winter’s Signs,

The Arctick Circle lies immerst in Shade,

And vainly calls to feeble Stars for Aid:

Because the Eyes that from the Pole survey

The bellying Globe, scarce measure half the way,

The Orb still rising stops the Sight from far,

And whilst we forward look, we find a Bar:

For from the Eyes the Lines directly fall,

And Lines direct can n’er surround the Ball;

Therefore the Sun to those low Signs confin’d

Bearing all Day and leaving Night behind,

To those that from the Pole survey denies

His chearful Face, and Darkness fills their Eyes:

Till having spent as many Months, as past

Thro’ Signs, he turns, and riseth to the North at last:

And thus, in this Position of the Sphere

One only Day, one only Night appear

On either side the Line, and make the Year.

Manilius clearly tells us that, at the Poles, six months of full light are followed by six months of full dark. Because of this, the Signs never rise and set at an “equal height” – which we know, today, is because the Earth appears tilted at the Poles. Manilius also understood this, as he compared the Earth at the Poles to a spinning top: “The World would seem, if we survey’d the whole / Erect, and standing on the nether Pole. / Its sides, as when a Top spins round, incline / Nor here nor there, but keep an even Line.”

That Manilius identified circumpolar reality with so much precision as early as the 1st century CE is not that surprising, since the spherical nature and tilted nature of the Earth’s polar axis had been known since the time of Eratosthenes (276-195 BCE). Eratosthenes was the first geometer/philosopher to propose the spherical nature of the Earth. His calculation of the axial tilt of the Earth at 23.85° was remarkably close to the 23.44° tilt assigned by modern science – unsurprising, when you consider that he estimated the Earth’s circumference as ~25,000 miles (it is 24,901 miles).

So, by the time Manilius wrote Astronomica, the spherical nature of the Earth, its axial tilt, and the impact of the tilt on the amount of day and night in the polar regions was well known. It is, therefore, less surprising that Manilius was so adamant that the Signs cannot be equally divided into houses – especially not at the Poles.

Manilius makes it even clearer that he is not using Whole Sign or Equal House when he says “and Lines direct can ne’r surround the Ball” in the polar regions. He is clearly telling us that the astrological charts of the polar regions can never look like those at the equator or even like those that during the equinox allow for equal houses.

Because the polar regions experience the extremes of day and night, the charts for those regions can never hold equal houses – though, like all charts, the horizon splits the chart into day and night. In the summer months, the Sun is always above the horizon in a chart. In the winter months, the Sun is always below the horizon in a chart. The ascendant-descendant line marks the transition between day and night in the polar regions, the short transitionary period between six months of day and six months of night.

Conclusion

Manilius’s Astronomica is a precise record of a method rooted in the spherical geometry of the Earth and the realities of geographical variation. From his rejection of the Chaldean system that assigns two hours to each sign, to his intricate depictions of the sky from the poles, Manilius presents an elegant astrology based on quadrants and unequal houses.

To ignore Manilius because his system is “inconvenient” or “anomalous” (a logical fallacy already addressed) does a disservice to the history of astrology. Astronomica was hand-copied, preserved, and translated across millennia because the knowledge within its five books mattered. The astrology Manilius describes integrates the tilt of the Earth, seasonal variance, and the staggered rising and setting times of the signs to yield a precise, geometrically faithful charting method.

What Manilius offers is an inheritance that demands attention. His work directly contradicts the claims of Hellenic revivalists who insist Whole Sign was the only system used in antiquity. Astronomica proves that at least one ancient astrologer (and likely more) understood that the zodiac is oblique, that geography alters house shape, and that the visible sky shifts from every point on Earth.

Manilius’s system reveals a fundamental truth that many modern revivalists would prefer remain hidden: so-called “Hellenic astrology” is not a comprehensive return to ancient practice, but a selective restoration of Ptolemaic astrology. And Ptolemy, writing later than Manilius, does not represent the totality of ancient astrological knowledge. That Manilius’s text is the only surviving one from the period outlining a fully formed alternative does not make it “anomalous.” In fact, the opposite is true.

Rome did not spend resources hand-copying obscure novelties. Texts were preserved and disseminated because they were valued. “Anomalous” texts do not survive through translation and transmission across centuries. The notion of “anomaly” in an already-fragmented historical record is a profound misreading – and misunderstanding – of history.

©The Knotty Occultist 2020-2025